Manzanitas are the “rock stars” of woody shrub diversity in California. Ranging from the Sierra Nevada mountains to the coastal bluffs along the Pacific, from temperate rainforests along the north coast to arid mountain slopes in Southern California, a wealth of manzanita species and subspecies can be found in an astonishing array of environments. Manzanitas occur on serpentines, dunes, volcanic soils, sandstone outcrops, dense shale, granite, gabbro–the list goes on. Central Coast manzanitas are some of the most diverse in the world.

Manzanita Ecology

Even with this astounding species and habitat diversity, there are common denominators that characterize this group. Most manzanitas depend upon fire for their regeneration. This is the key to why manzanitas are so prominent in the Mediterranean-type climate of California. Here, high-severity (in addition to mixed- and low-severity) wildfires have shaped the region during its long summer dry season. Another common feature of most manzanitas is that they occur, and often dominate, California’s evergreen fire-adapted shrubland known as chaparral. Similar shrublands are found in only four other regions on the planet (see next section for more information). Finally, while manzanitas are found on a wide variety of substrates, preferred soils are typically shallow, rocky, and/or nutrient poor.

The vast majority of Arctostaphylos taxa are found within the California Floristic Province, an area that encompasses southwestern Oregon, much of California (excluding the deserts), and northern Baja California .

— Field Guide to Manzanitas

Regional Endemism

The vast majority of Arctostaphylos taxa are found within the California Floristic Province (CFP), an area that encompasses southwestern Oregon, much of California (excluding the deserts), and northern Baja California (fig. 1). This area effectively represents the Mediterranean-type climate region in North America and Mexico wherein 104/105 (99%) of Arctostaphylos are found with only seven of these taxa (6%) (A. uva-ursi subsp. uva-ursi & subsp. cratericola, A. nevadensis, A. columbiana, A. patula, A. pungens, A. pringlei subsp. pringlei) extending beyond the CFP. Of these 104 taxa, 62 (60%) are considered local endemics; i.e., taxa whose distribution covers less than 1000 square km (an area less than 20 miles by 20 miles). Further, of these 62 local endemic taxa, 49 (82%) are found in near-proximity to the Pacific Coast. This richness of local endemics, particularly along the California coast, makes manzanitas exciting to observe, challenging to identify, and important from a conservation perspective.

Central Coast Manzanitas

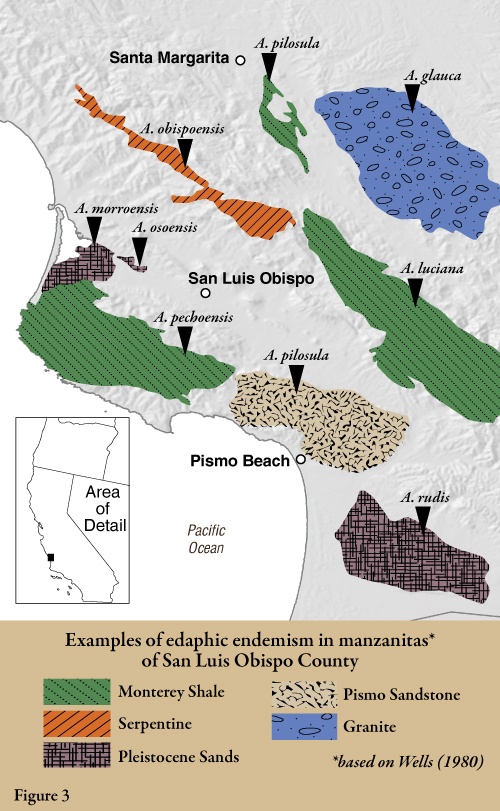

Manzanitas tend to occur in sites with poorly developed, usually low nutrient soils. Mycorrhizal fungi are a principal reason manzanitas can tolerate these low nutrient conditions. They also thrive where fire frequency is high. Although fire regimes are one key to species diversity in manzanitas, it is not the only reason for their diversity. Because so many manzanitas are local endemics found along the California coast, it is instructive to consider what may be the driving forces shaping endemism in this region. Due to tectonic activity, shallow, rocky, nutrient-poor soils often occur as “edaphic islands” embedded within a matrix of deeper and more fertile soils. The coast also presents a steep climate gradient during the summer, ranging from cool and moist conditions at low elevations near the ocean to hot and dry conditions on inland ridges and slopes. Forest, coastal scrub, and grassland tend to dominate vegetation along the coast whereas chaparral is typically confined to the edaphic islands (fig. 3). Over time, especially during the Ice Ages, some have proposed that different manzanita species may have migrated onto and off of these soil islands during climatic oscillations.

San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara counties exhibit a high level of endemics and species diversity of manzanitas due to all these factors.

Manzanitas of San Luis Obispo County

- crustacea subsp. crustacea

- cruzensis*

- hookeri subsp. hearstiorum*

- glandulosa subsp. glandulosa

- glandulosa subsp. cushingiana

- glauca

- luciana*

- morroensis*

- obispoensis

- osoensis*

- pechoensis*

- pilosula*

- pungens

- rudis

- tomentosa subsp. tomentosa

- tomentosa subsp. daciticola*

Manzanitas of Santa Barbara County

- confertiflora*

- crustacea subsp. crustacea

- crustacea subsp. eastwoodiana*

- crustacea subsp. insulicola*

- crustacea subsp. subcordata*

- glandulosa subsp. glandulosa

- glandulosa subsp. cushingiana

- glandulosa subsp. mollis

- insularis*

- parrayana subsp. parrayana

- pungens

- purissima*

- refugioensis*

- rudis

- viridissima*

* are county endemics

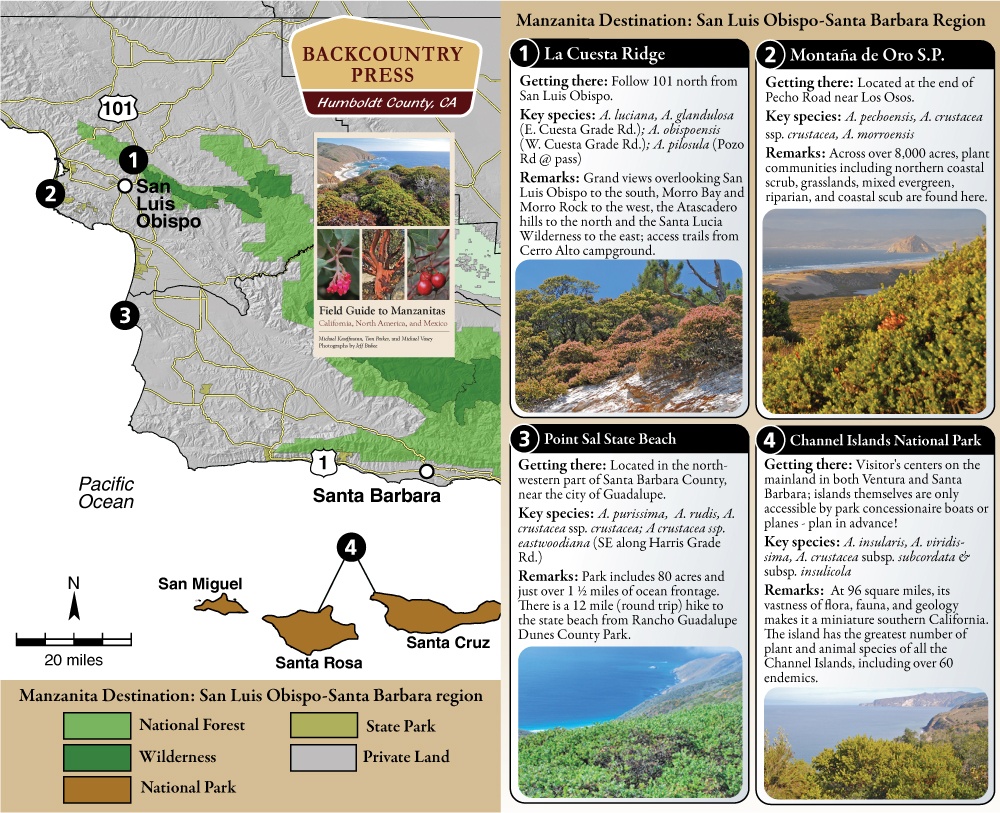

Visit the Central Coast Manzanitas

In the book, it says to “Visit our website (manzanitas.backcountrypress.com) to find lists of species within these lineages.” That didn’t work, and the 2 links on this page don’t work either.

Thanks Leif- finally got around to fixing the links on the new reference page. We are working to redirect the website referenced in the book.

Thanks! I downloaded those 2 pdfs, but they didn’t have what was referred to in the book about a list of which diploid species have deep related lineages, and thus can more easily hybridize with each other.

I second that. It would be an incredible resource to have those lists of related lineages for deciphering what is possibly hybridizing in the field where ranges overlap!

And thank you for such a phenomenal resource!

I am also interested in the list of species by lineage and have not been able to find it here; please let me know where I may find it/if it’s eventually posted. Thank you for the wonderful book!

For SLO and Santa Barbara Counties, almost all the taxa are from a single lineage. Only A. rudis in Santa Barbara County, and A. hookeri subsp. hearstiorum from SLO Co. are in a separate lineage. That just means that hybridization among taxa is easy if they’re close together, just difficult for two taxa of the same lineage but not impossible. It’s a messy group that’s quite flexible and exchanges genes readily.

Minor correction to the above, A. rudis is also found in southern San Luis Obispo County on the Nipomo Mesa, another ancient sand mesa similar to Burton Mesa near Lompoc.

ALSO found in SLO County, as well as Santa Barbara County