Today, we embark on a flavorful journey through the lush forests of the Pacific Northwest, where the evergreen trees are not only charismatic megaflora, but also potential ingredients for a unique tea experience. Let’s raise our teacups to the wonders of nature with a botanical twist. Join me on an adventure to brew teas using various conifer species found in the varied landscapes of Cascadia.

Before we dive into the surprisingly delightful world of coniferous infusions, let’s take a moment to discuss some precautions and considerations. You may be saying to yourself:

Conifer tea, eh? Well which species can I use?

The answer is simple: All of them… with one notable exception.

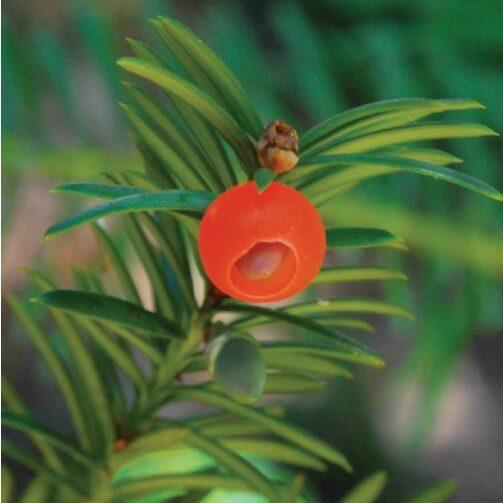

Avoid using any Yew species as parts of this plant are poisonous. Pacific Yew (Taxus brevifolia) is native to the PNW but additional species are planted as ornamentals throughout the region. The needles resemble that of the Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), but the stature of the tree/shrub is much (potentially MUCH) scrawnier than its cousin. Obviously please avoid harvesting from any places where you are not allowed to collect plants. And ALWAYS make sure you have correctly identified a plant (or mushroom!) before choosing to ingest it

Need help identifying your conifers?

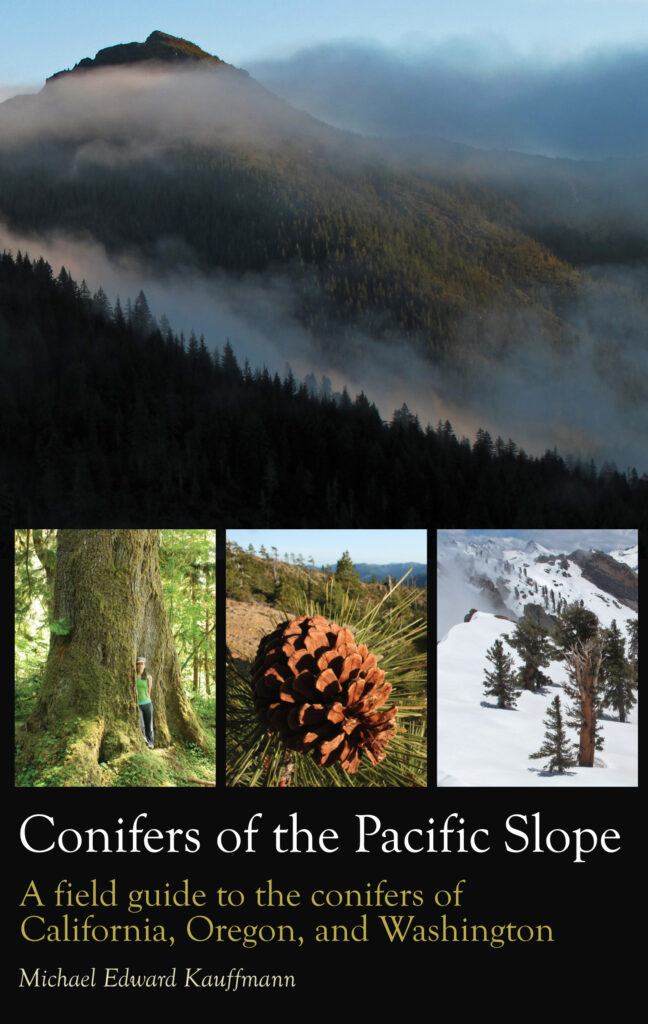

Check out our field guide: Conifers of the Pacific Slope.

Participants in the Mushrooms of Cascadia class get 40% off with the coupon code found on the Class Resources page.

How to make a great cup of conifer tea:

- Gather a handful of fresh, young conifer needles from your favorite coniferous (non-yew!) neighbor

- Give them a few snips if needed so they fit in your Mason jar or tea pot

- Boil a pint of water

- Pour over your conifer bits, cover with a lid so those delightful volatile oils don’t just fill the airspace of your room, and allow to steep 10 to 20 minutes

- Strain if you like and enjoy!

Let’s get to those conifers

Douglas-fir

Our first stop is with the iconic Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), found from British Columbia through Northern California with a few stands farther to the south. To prepare Douglas-fir tea, gather fresh, young tips preferably in the Spring, but honestly these make a delicious tea year-round. The needles impart the most lovely, delicate, citrusy zing to your tea. This year we gathered Douglas-fir tips on our pre-Thanksgiving meal stroll, then brewed them up for an after meal tea. A real crowd pleaser!

Western Redcedar

Next, let’s embrace the aromatic essence of cedar. Western redcedar (Thuja plicata) is your go-to species. Collect a handful of young tips (needles and twigs). Infuse the cedar bits in hot water, creating a fragrant tea with earthy undertones.

If yellow-cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis) is abundant in your neck of the woods, you can enjoy that as well!

Sitka Spruce

Venture into the realm of spruces, such as the Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis). You’ll find these region defining conifers growing from Kodiak Island Alaska to Mendocino County, California. Harvest the bright green tips in (ideally) spring for a zesty, citrus-infused tea. The young shoots are packed with vitamin C, making this brew not only flavorful but potentially beneficial for your immune system. Enjoy the surprise of flavors dancing on your palate imparted by these especially sharp-tipped needles!

Juniper

Now, let’s turn our attention to the junipers (Juniperus spp.), seven species of which grow along the Pacific Slope! These hardy evergreens provide us with berries that can add a delightful twist to your tea. Crush a few juniper berries and infuse them in hot water. The result is a warm, slightly spicy concoction that pairs well with a drizzle of honey.

Pines

Let’s celebrate the versatility of Pine trees (Pinus spp.). Whether it’s a ponderosa (P. ponderosa), lodgepole (P. contorta), western white (P. monticola), ghost pine (P. sabiniana) or any other of the 21 species that grow along the Pacific Slope, the needles are fair game… except for maybe one that is able to eke out an existence at high elevation.

I’m looking at you foxtail (P. balfouriana), whitebark (P. albicaulis), limber (P. flexilis), and bristlecone (P. longaeva). We’ll let you be.

Gather a handful of fresh pine needles, avoiding any that appear brown or damaged. If your hand is filled with especially long needles (like ponderosa or Jeffrey) you may want to cut them up a bit before putting in your vessel of choice. The resulting tea boasts a crisp, resinous flavor, reminiscent of a walk in the evergreen-scented air.

Redwood

Last but not least, the majestic redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens)! Perhaps not the tree that first pops in your head when you think of the Pacific Northwest, but these tallest trees in the world hug the cool coastal fog belt of the Pacific coast up into Oregon. The soft, feathery needles of these giants can be used to create a mild, slightly sweet infusion reminiscent of the damp rainforest’s invigorating scent.

Cheers

As we wrap up this forest tea journey, raise your teacup to the incredible diversity of conifer species in the Pacific Northwest. From the citrusy notes of Douglas-fir to the earthy aroma of western redcedar, each sip is a reminder of the wonders that surround us in nature. Cheers!

Leave a Reply